So of course in the midst of everything, the state of the world being what it is, humanity on the cusp of extinction, here I am writing another email about sex and friendship. What else is there to live for?

Alice writes this to her best friend, Eileen in an email. There’s something very romantic about the idea of finding beauty in our connections with other people who are also aware of uncertainties and, oftentimes, the ugliness of life. That the beauty in life comes from the small microcosms that we form with our loved ones, friends, and sometimes strangers who metamorphose into someone immeasurably important.

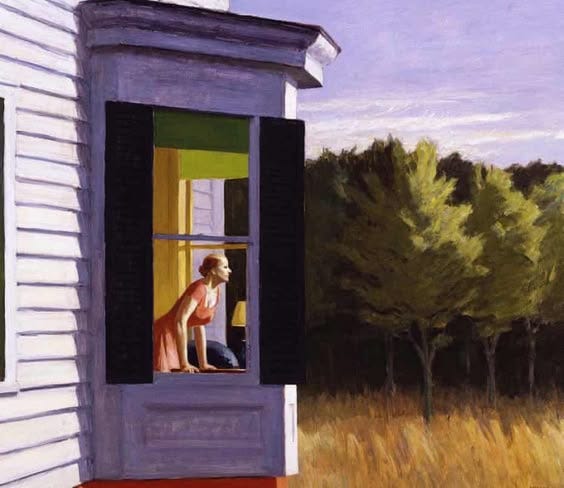

How do we find a beautiful world among us, despite everything? In Sally Rooney’s Beautiful World, Where Are You, she argues that the word despite is the most crucial part of this question. That despite everything, there’s still much beauty in the world to live for. In a lonely and ever-changing world, nothing is permanent and everything is precarious. An apocalypse may happen tomorrow, and everything we hold dear may vanish into thin air. Alice and Eileen, best friends who live away from each other, explore this thought through multiple examples: from single use plastic to lost ancient languages.

Beautiful World, Where Are You centers around four people in their twenties and thirties: Alice and Eileen, who are best friends, along with their respective romantic interests, Felix and Simon. It is a bildungsroman in a way, since all four of them are still trying to figure out how to find their own places in society while simultaneously growing into their own skin. The pair of best friends are on the cusp of turning 30 and are still trying to grow up as they get older. Alice is a famous novelist who is suffering from writer’s block. She grapples with her private life bleeding into her fame; when the novel starts, she has recently been committed to an institution after a breakdown.

“I find my own work morally and politically worthless,” she writes to Eileen in an email. “I never advertised myself as a psychologically robust person, capable of withstanding extensive public inquiries into my personality and upbringing,” she says in another. Alice mirrors Rooney in many ways, who has publicly spoken about how the level of scrutiny and attention she receives as a person outside of her novels. Her worries border on existential as she wonders if what she has done in her life is too trivial and inconsequential. Or on a bigger scale, if anything she does in the future will be inconsequential.

Eileen worries about this as well, mostly in reply to Alice. Through their emails and in their day-to-day lives, they try to find the meaning of life and meaning amid the commodification of art and beauty. If these things are bolstered in a capitalistic society, are they still beautiful? Eileen, a publishing assistant, starts a romance with her childhood friend, Simon. They both struggle to express their true emotions and intentions with each other; their relationship is wrought with misunderstandings. In a way, Eileen and Simon represent the theme and message of this book: everything is messy and sometimes dysfunctional, yet we still crave human connection and intimacy and an opportunity to love in earnest.

In the book, Rooney accomplishes something that I think is very remarkable: she builds four characters without a trace of her own authorial voice, instead slipping into her role as an observer as if she has encountered these characters in real life. In the 400 pages, between the first and last page, they exist as real people. They live and breathe and worry and make mistakes and do things right. It almost feels like Rooney created them and then left them to fully transform into humans within the course of the book. Her writing is often seen as clinical because of this—most of the book focuses on dialogue and actions of characters, leaving it to readers to read between the lines and fill in the introspection.

“What if the meaning of life on Earth is not eternal progress toward some unspecified goal—the engineering and production of more and more powerful technologies, the development of more and more complex and abstruse cultural forms? What if these things just rise and recede naturally, like tides, while the meaning of life remains the same always—just to live and be with other people?”

As readers, we are only observers in Alice and Eileen’s actual chapters that are written in a third-person-limited point of view, but we are able to read their exact, straightforward thoughts through the emails they send each other. This is an interesting creative choice by Rooney: the only time we are able to truly know what they are feeling is through emails, in which we are reading what was written about their writing. It almost feels like the fourth wall breaking.

Even in the emails, however, we as readers, are required to make sense of them. Alice and Eileen intellectualize their worries through historical, scientific, or political anecdotes. They are best friends after all, so tangents are common, jumping from personal updates to discussions about the Late Bronze Age collapse. Rooney does lace a common theme between these varying topics, but she leaves it up to us to fully understand their thoughts. The pair of friends write to each other, unaware that they have an audience.

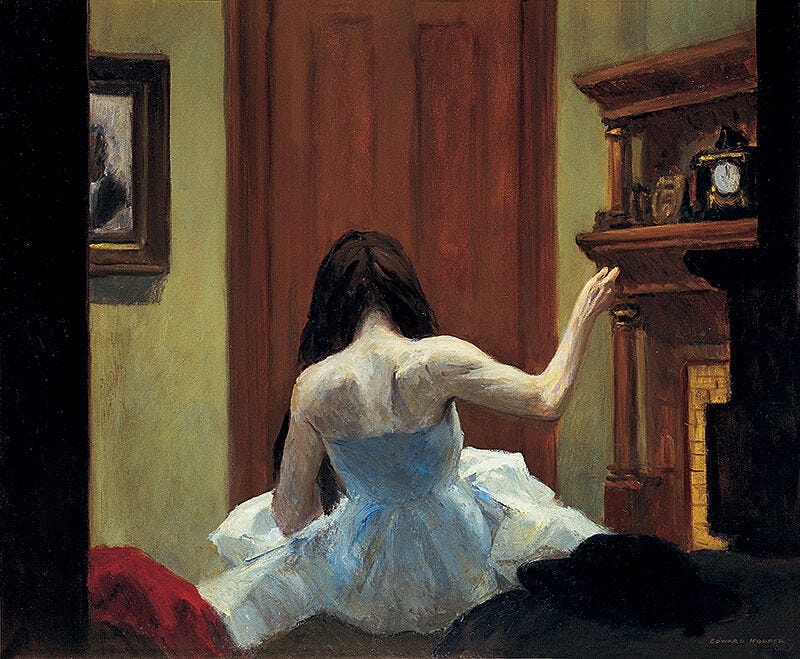

While they do worry about ‘greater’ things in their emails, Alice and Eileen’s day to day lives are deeply and painfully ordinary like the rest of us. They worry about their jobs, meet new people, have sex, fall in love. Even in the face of potential societal collapse, they struggle to verbalize their feelings, stay in dead-end jobs, and have fights over trivial matters. It is almost as if Rooney is saying that in the end, this is most of what we will think and worry about—and that is completely fine.

The heart of the book is the friendship between Alice and Eileen, and their relationships. They create their own beautiful world—because that is what makes life worth living and even enjoyable. Rooney puts forth an idea that may be buried in the melancholy and pitfalls of blue emotions. It is something that is so extraordinarily optimistic: that the world is beautiful because we have each other and we have the ability to love, and it will remain beautiful, despite everything.

Maybe we're just born to love and worry about the people we know and to go on loving and worrying even when there are more important things we should be doing. And if that means the human species is going to die out, isn't it in a way a nice reason to die out, the nicest reason you can imagine? Because when we should have been reorganizing the distribution of the world's resources and transitioning collectively to a sustainable economic model, we were worrying about sex and friendship instead. Because we loved each other too much and found each other too interesting. And I love that about humanity, and in fact it's the very reason I root for us to survive - because we are so stupid about each other.

i ADORE BWWAY and your interpretations of it are so beautiful to read!! i love your point about rooney writing the characters from the side, as if describing people she knows and in the context of the novel it makes perfect sense! a great read 🥹💌

ugh love love love the way your described this book I need to go and read it right away